What Is a Call Option?

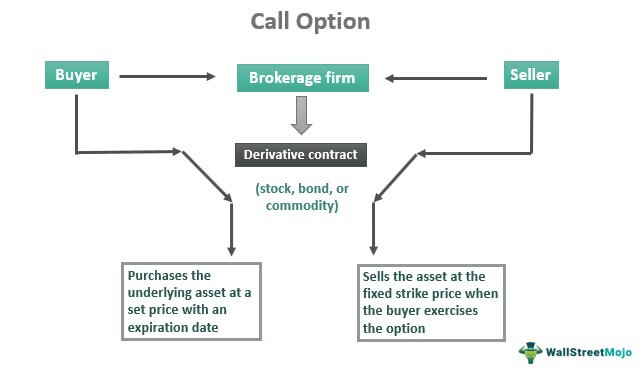

Call options are financial contracts that grant the buyer the right but not the obligation to buy the underlying stock, bond, commodity, or instrument at a specified price by a specific date. In general, a call buyer profits when the underlying asset increases in price.

On the opposite end, there are put options, which gives the holder the right to sell the underlying asset at a specified price on or before a specified expiration date.

Understanding Call Options

Let’s assume the underlying asset is a publicly traded stock. Call options grant the holder the right, but not obligation, to buy 100 shares of that stock at a specific price (strike price), up until a specified date (expiration date.)

For example, a single call option contract may give a holder the right to buy 100 shares of Microsoft ($MSFT) stock at $250 up until the expiration date two months later. This is just one of many different choices as there are many expiration dates and strike prices that traders can choose.

As the value of $MSFT stock goes up, the price of the option contract goes up, and vice versa. The option buyer may hold the contract until the expiration date, at which point they will have one of two choices:

Purchase the underlying stock at a discounted price (strike price)

Sell the options contract at any point before the expiration date at the market price of the contract at that time.

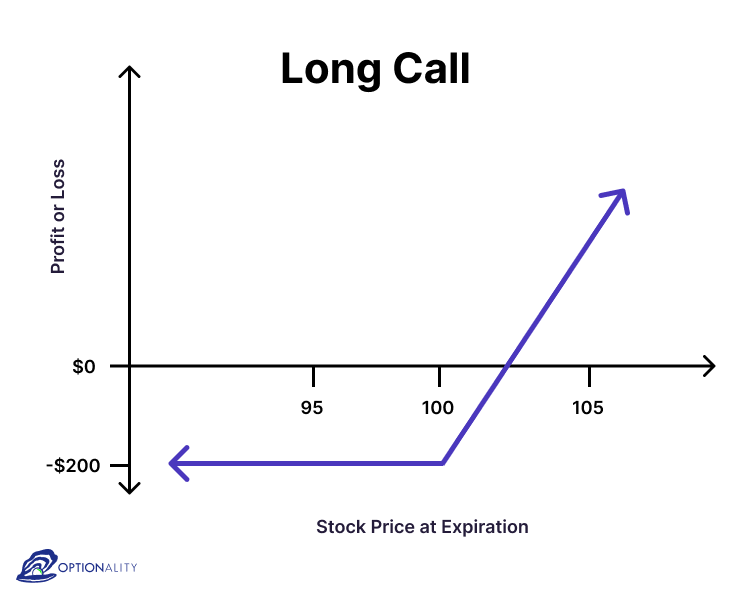

A trader pays a fee to purchase a call option, called the premium. It is the price paid for the rights that the call option provides (i.e. the price to draft the contract and its terms). If at expiration the underlying stock price is below the strike price, the call buyer loses the premium paid. This is the maximum loss.

If the underlying stock’s current price is above the strike price at expiration, the profit is the difference in prices, minus the premium. This sum is then multiplied by how many contracts the option buyer initially bought.

For example, if Apple is trading at $110 at the expiration date, the option contract strike price is $100, and the options cost the buyer $2 per share (or $200 in total), the profit is $110 – ($100 +$2) = $8. If the buyer bought one options contract, their profit equates to $800 ($8 x 100 shares); the profit would be $1,600 if they bought two contracts ($8 x 200).

On the other hand, if Apple is trading below $100 at expiration, then obviously the buyer won’t exercise the option to buy the shares at $100 apiece, and the option expires worthless. The buyer loses $2 per share, or $200, for each contract they bought – equal to their maximum loss

Long vs. Short Call Options

There are two basic ways to trade call options.

Long call option: A long call option is your standard call option in which the buyer has the right, but not the obligation, to purchase the underlying stock at a strike price in the future. The advantage of a long call is that it allows the trader to plan ahead to purchase a stock at a cheaper price. For example, you might purchase a long call option in anticipation of an upcoming event, say a company’s earnings call. While the profits on a long call option may be unlimited, the losses are limited to the premiums on the contracts. Thus, even if a company does not report a positive earnings beat and the price of its shares declines, the maximum losses that the buyer of a call option will endure are limited to the premiums paid for the option.

Short call option: A short call option is the opposite of a long call option. In fact, these are the contracts that traders sell to those who purchase long call options in the above example. In a short call option, the seller promises to sell their shares at a fixed strike price in the future. Short call options are mainly used for covered call strategies by the option seller, or call options in which the seller already owns the underlying stock for their options. The call helps mitigate the losses that they might suffer if the trade doesn’t go their way.

How to Calculate Call Option Payoffs

There are three key variables to consider when evaluating call options: strike price, expiration date, and premium.

These variables calculate payoffs generated from call options. There are two cases of call option payoffs.

Payoffs for Call Option Buyers

Suppose you purchase a call option for company ABC for a premium of $2 per share or $200 in total. The option’s strike price is $60, and it has an expiration date of Nov. 30. Your option will break even if ABC’s stock price reaches $62—meaning the sum of the premium paid plus the stock’s purchase price. Any increase above that amount is considered a profit. Thus, the payoff when ABC’s share price increases in value is unlimited.

What happens if ABC’s price declines below $60 by Nov. 30? Since your options contract is not an obligation, you can choose to not exercise it, meaning you will not buy ABC’s shares. Your losses, in this case, will be limited to the premium you paid for the option, or $200.

Payoff = spot price – strike price

Profit = payoff – premium paid

Using the formula above, your profit is $3 per share ($300 in total) if ABC’s spot price is $65 on Nov. 30.

Payoff for Call Option Sellers

The payoff calculations for the seller for a call option are not very different. If you sell an ABC options contract with the same strike price and expiration date, you stand to gain only if the price declines. Depending on whether your call is covered or naked, your losses could be limited or unlimited. The latter case occurs when you are forced to purchase the underlying stock at spot prices (or, perhaps, even more) if the options buyer exercises the contract. Your sole source of income (and profits) in this case is limited to the premium you collect on expiration of the options contract.

The formulas for calculating payoffs and profits are as follows:

Payoff = spot price – strike price

Profit = payoff + premium

There are several factors to keep in mind when it comes to selling call options. Be sure you fully understand an option contract’s value and profitability when considering a trade, or else you risk the stock rallying too high.

Uses of Call Options

Call options often serve three primary purposes: income generation, speculation, and tax management.

Using Covered Calls for Income

Some investors use call options to generate income through a covered call strategy. This strategy involves owning an underlying stock while at the same time selling a call option, or selling the rights to someone else to buy your stock. The investor collects the option premium and hopes the option expires worthless (below strike price). This strategy generates additional income for the investor but can also limit profit potential if they are forced to prematurely sell their stock if the underlying stock price rises sharply.

Covered calls work because if the stock rises above the strike price, the option buyer will exercise their right to buy the stock at the lower strike price. This means the option writer doesn’t profit from the stock’s movement above the strike price. The options writer’s maximum profit on the option is the premium that was received.

Using Calls for Speculation

Options contracts give buyers the opportunity to gain exposure to a stock for a relatively small price. They can provide significant gains if a stock rises. However, traders must be aware that options can also result in a 100% loss of the premium if the call option expires worthless due to the underlying stock price failing to move above the strike price in time. The benefit of buying call options is that risk is always capped at the premium paid for the option.

Investors may also combine buying and selling different call options simultaneously, creating a call spread. These will cap both the potential profit and loss from the strategy but are more risk-averse and cost-effective in some cases than a single call option.

Using Options for Tax Management

Investors sometimes use options to change allocations within their portfolio without actually buying or selling the underlying security.

For example, an investor owns 100 shares of XYZ stock and is liable for a large unrealized capital gain. Not wanting to trigger a taxable event, this investor may utilize options to reduce the exposure to the underlying security without actually selling it. The only cost to the shareholder for engaging in this strategy is the cost of the options contract itself.

Though options profits will be classified as short-term capital gains, the method for calculating the tax liability will vary by the exact option strategy and holding period.

Example of a Call Option

Suppose that AMD stock is trading at $108 per share. You own 100 shares of the stock and want to generate an income above and beyond the stock’s dividend. You also believe that shares are unlikely to rise above $115 per share over the next month.

You take a look at the call options for the following month and see that there’s a 115 call trading at 37 cents per contract. So, you sell one call option and collect the $37 premium (37 cents x 100 shares), representing a roughly 4% annualized income.

If the stock rises above $115, the option buyer will exercise the option, and you will have to deliver the 100 shares of stock at $115 per share. You still generated a profit of $7 per share, but you will have missed out on any upside above $115. If the stock doesn’t rise above $115, you keep the shares and the $37 in premium income.

How Do Call Options Work?

Call options are a type of derivative contract that gives the holder the right but not the obligation to purchase a specified number of shares at a predetermined price, known as the “strike price” of the option. If the market price of the stock rises above the option’s strike price, the option holder can exercise the option, buying at the strike price and selling at the higher market price in order to lock in a profit. All options have an expiration date. If the market price does not rise above the strike price during that period, the options expire worthless.

Why Would You Buy a Call Option?

Investors will consider buying call options if they are bullish about the future price movement of its underlying shares. Call options might provide a more attractive way to speculate on the prospects of a company because of the leverage that they provide. After all, each contract provides the opportunity to buy 100 shares of the company in question. For an investor who is confident that a company’s stock will rise, buying call options can be an attractive way to increase their purchasing power.

Is Buying a Call Bullish or Bearish?

Buying calls is a bullish strategy because the buyer only profits if the price of the shares rises. Conversely, selling call options is bearish, because the seller profits if the shares do not rise too much. Whereas the profits of a call buyer are theoretically unlimited, the profits of a call seller are limited to the premium they receive when they sell the calls.